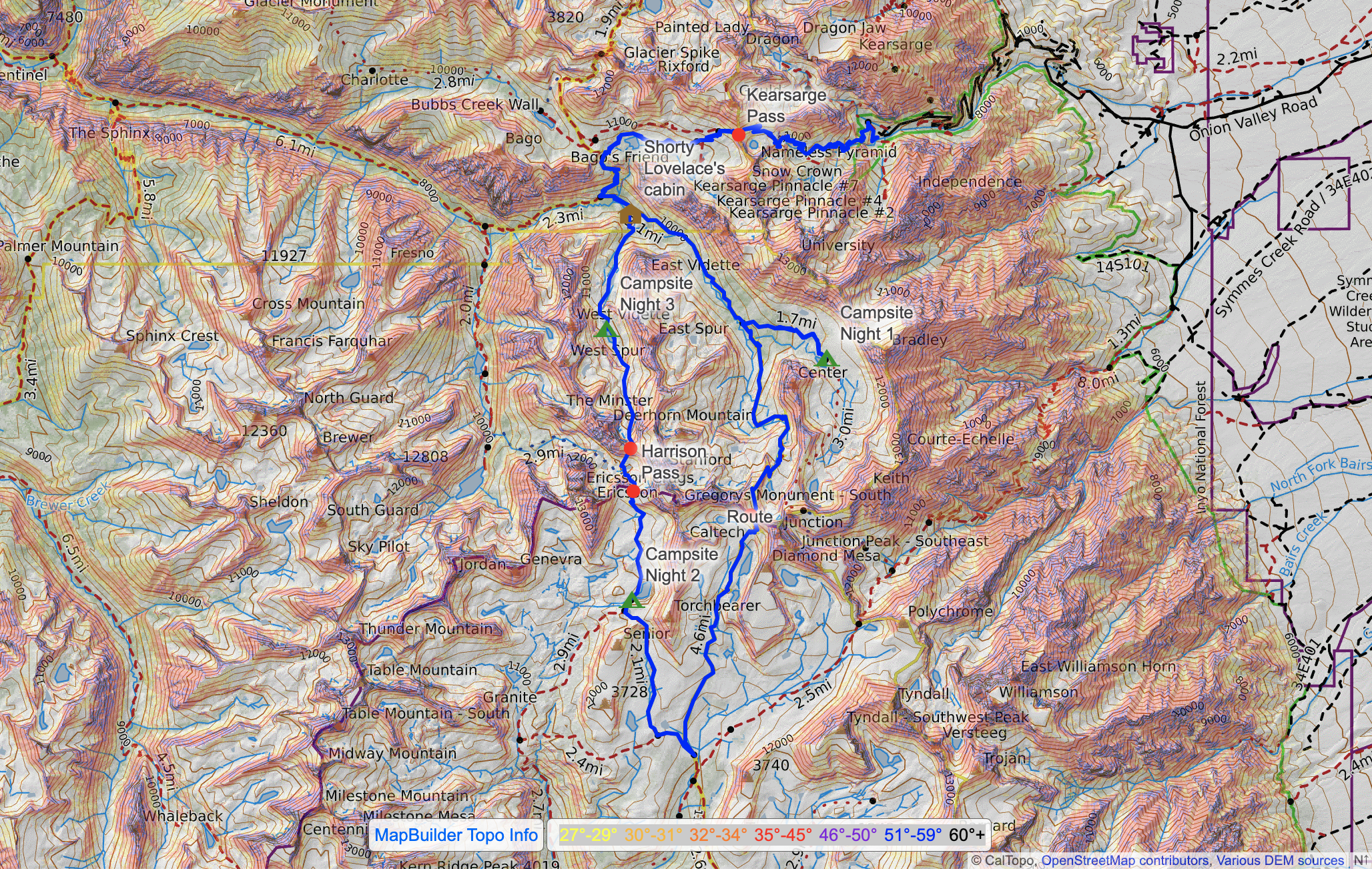

Kearsarge Pass to Center Basin, Lake South America, and Vidette Lakes

Trip Breakdown

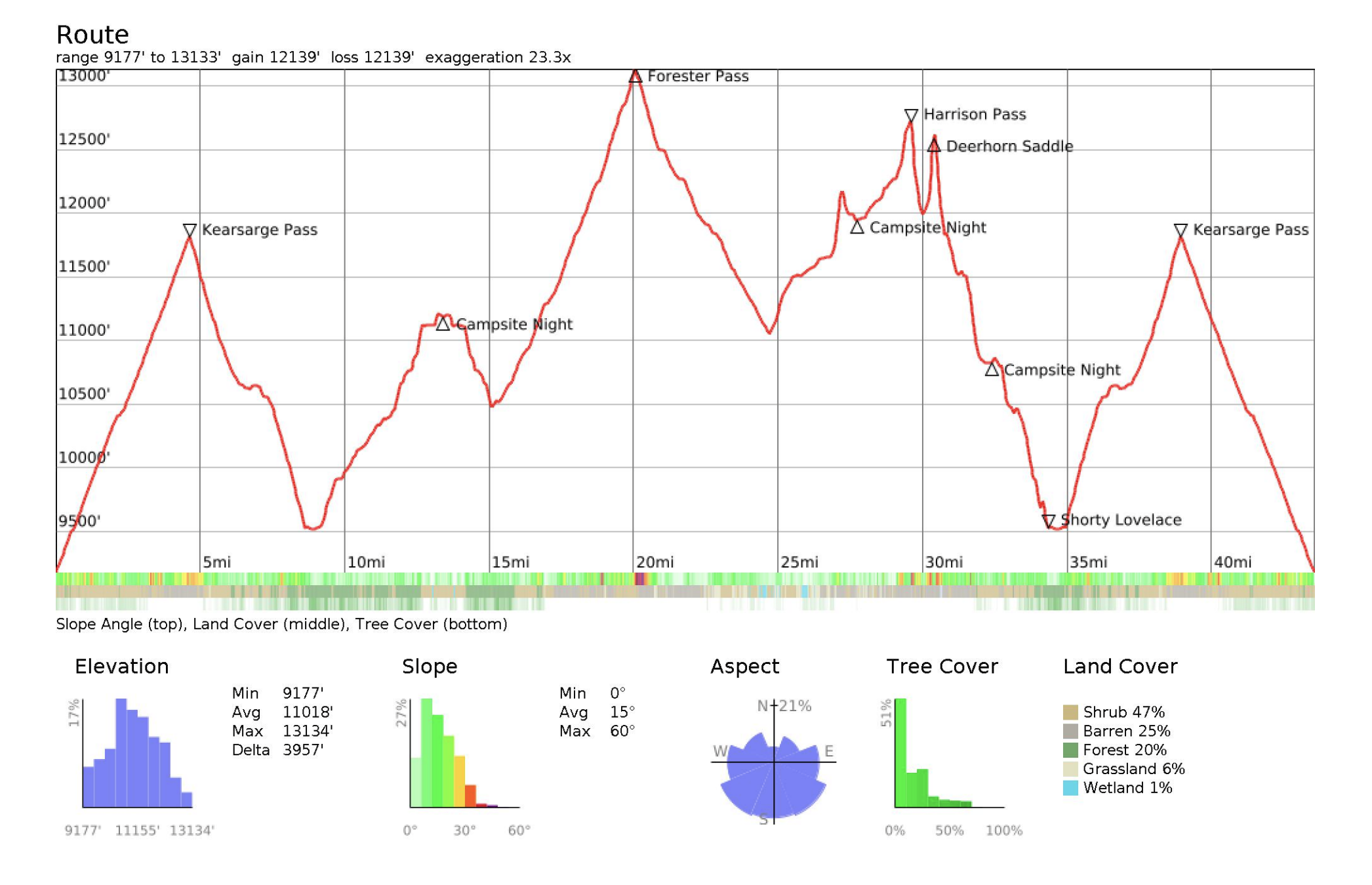

Difficulty Rating: Strenuous Days/Nights: 4/3 Distance: 43.58 mi

Elevation Range: 9,177' to 13,134' Total Elevation Gain/Loss: +12142' -12142'

Time of Year: mid-September 2025 Snowpack: 84% (Southern Sierra - Below Average)

The Good: Stunning scenery from start to finish, with Center Basin and Upper Vidette Lake as highlights.

The Bad: Sketchy descent of Harrison Pass (off-trail); thawing the tent every morning.

Marmot sightings: 18

A Brief Trail Preview

Kearsarge Pass is a coveted permit for good reason. The access-to-difficulty ratio is hard to beat in the Eastern Sierra. Inyo National Forest offers a whopping 60 permits a day and it is often still difficult to snag a permit most weekends.

The climb from Onion Valley to the pass (11,760 ft) is a scenic and gradual ascent, passing many lakes along the way. The trail offers easy routes to popular destinations like Rae Lakes and Sixty Lakes Basin.

For this trip, we headed south, having already backpacked the Rae Lakes area earlier in the summer via Baxter Pass. We made a loop connecting Center Basin, Lake South America, and the Vidette Lakes area via two off-trail passes: Harrison Pass and Deerhorn Saddle.

Trail Dairy

The last backpacking trip of the season! We booked it up to Onion Valley after work, arriving around midnight and catching a few Z’s at the Onion Valley campground before hitting the trail the next morning. I’ve never seen so much parking at an eastside trailhead (outside of Mammoth) and the trail from the start was buzzing with hikers.

The trailhead sits at 9,100 ft and from there the trail zigzags up 2,660 feet to Kearsarge Pass, where the jagged saddle opens up to views of Kearsarge Lakes below.

The trail shed elevation quickly as we dropped into the Kearsarge Lakes zone. We took a snack break at Bullfrog Lake, with our first glimpse of the impressive East Vidette, which we were to orbit around the entire trip.

To note: After years of overuse, no overnight camping is permitted at Bullfrog Lake (or within ¼ mile of it), a tragedy of the commons.

The conditions all day were moody and the commencement of fall in the Sierra was underway. I love witnessing the shift of seasons out there. Bullfrog Lake was especially flush with fall color, as the lake rim was lined with a mat of reddish grass in mid-September.

Bear Beware!

The Charlotte Lake backcountry ranger posted a witty sign warning hikers about recent bear activity in the area. The nearby Rae Lakes area has long held a reputation as a bear hotspot, home to a population that’s become “food-conditioned” thanks to the steady flow of backpackers (and their snacks).

After Bullfrog Lake, we linked up with the JMT and headed south towards Center Basin. The trail into the basin isn’t marked on our National Geographic map but an old unmaintained trail does exist. The turn off is not obvious, so we used our Garmin Explore app to locate the junction. The trail (once located) is in great condition and very easy to follow.

A quick history lesson: The Center Basin trail used to be apart of the old JMT before Forester Pass was blasted into existence in the early 1930s. The old route used to cut through Center Basin and go over Junction Pass and Shepherd Pass on the way to Mt. Whitney.

Along the way, we passed a bulletin tied to a pine tree explaining that Park Service biologists were conducting a restoration project in Center Basin. When we arrived at Golden Bear Lake, we spotted them floating on rafts in the middle of the water, checking gillnets for non-native fish. It was our second encounter of the summer with an aquatic restoration site for the endangered mountain yellow-legged frogs (Rana muscosa and Rana sierrae). The project is part of an NPS effort to return select basins to their naturally fishless condition so the frog populations can recover. You can read more about these conservation efforts here.

As we settled into camp, the moody pre-fall weather gave way to one of the most outstanding sunsets I’ve had the fortune of witnessing in the Sierra. No photo or video could do it justice. The clouds settling below us shifted from orange to pink to purple, and the sight brought tears to my eyes — the perfect ending to a perfect Sierra day!

The next morning we packed up our camp and made our way back to the JMT. Our objective of the day was to get to Lake South America via Forester Pass, the highest pass (13,200 ft) along the JMT. Forester is a feat of engineering and I was excited to check out how they made this route possible. The climb kept its sights on the imposing pass the whole way up, and we passed a delightful number of marmots en route. The final switchbacks spit us out at the notch, and I let out a triumphant whoop. Below us lay a dizzying view of the Bubbs Creek drainage to the north and the Tyndall Creek drainage to the south.

We stopped for lunch at an unnamed lake below the pass, framed by Caltech Peak. We devoured our tuna and goldfish wraps alongside fellow backpackers and some very habituated marmots. We didn’t linger long, as the dynamic skies had shifted to an ominous gray overhead. Thankfully, most of the climbing was behind us, and we could outpace the storm on the downhill.

Along this stretch, we crossed paths with another NPS employee who might just have my dream job. Her current assignment was to backpack to subalpine meadows and assess their condition, ensuring that the limited stock grazing permitted in Sequoia National Park isn’t harming these fragile ecosystems. Oh, to spend your days looking after the flowers… sigh!

As we continued, prominent peaks like Mount Tyndall disappeared into the clouds as they sank low and began pelting us with hail. I don’t particularly mind hail — it bounces right off without soaking your clothes. We eventually reached the turnoff for the Lake South America Trail and began the roughly 1,000-foot climb to its namesake lake.

The terrain opened into a steppe-like landscape, and Tanner joked that he felt like he’d just stepped (pun intended) into Mongolia. No Silk Road here, just a peaceful creek winding through an open grassy plain.

As we started the final climb toward the lake, we could no longer outrun the storm, and it began to snow. As we arrived at the lake, the storm broke just long enough for us to pitch the tent and dive inside before it returned in full force for the next ninety minutes. We reemerged well after sunset, once the storm had passed, and cooked dinner in the dark while gazing up at the stars in the now-clear sky above.

Fun fact: Lake South America is the headwater of the mighty Kern River.

The next morning, our tent fly was frozen stiff, so we got a late start to let it thaw. Tanner took the opportunity to do some fishing off the coast of “Brazil” and caught a vibrant California golden trout (Oncorhynchus aguabonita). Lake South America also has rainbows according to Fly Fishing the Sierra, which is a phenomenal resource on fishing the alpine lakes in the range.

Once the rain fly was sufficiently dry, we packed up camp and set off for our first off-trail pass of the day. When plotting our route, we had a few options for crossing the Kings–Kern Divide: Milly’s Foot (Class 3), Lucy’s Foot (Class 2–3), or Harrison Pass (Class 2). We consulted our backcountry bible The High Sierra: Peaks, Passes, Trails, 3rd Ed. for guidance in our decision. We opted for Harrison Pass for its proximity to Vidette Lakes and its lower class rating.

Harrison’s south side offered a steep but manageable climb to the pass, which took us about an hour and a half to get to from Lake South America. The pass, marked by an obnoxiously large cairn, offered a daunting view down the north side: a sheer slope of loose gravel and questionable footing.

Like many Sierra passes, the north-facing slopes tell a different story than their gentler southern approaches. The colder, shaded north sides hold snow longer, and over time, repeated freeze–thaw cycles have carved deeper into the granite, creating the eroded and steep terrain seen today.

After peering over the edge, I pulled out a Clif Bar and pondered all the life decisions that had brought me to this point.

As I now reread The High Sierra blurb on Harrison Pass, I can’t say we weren’t warned: “This trail has not been maintained for many years, and the critical portion leading up the north side of the pass has all but disappeared.” I also learned Harrison is an “old sheep route”, never meant “for mere mortals”. Bah, humbug!

Channeling all my past off-trail pass experience into a false confidence, I convinced myself that surely it couldn’t be worse than Cataract Pass (more on that in a future blog post) and started making my way down the shaded east side of the pass.

Tanner began descending the west side to avoid the patches of snow, but quickly regretted it as the eroded slope began slipping under his feet. To get out of his hairy predicament, he humbly sat down and scooted over to me on his bum. Once we reunited and collected ourselves, we discussed how to proceed. Going back up to backtrack almost looked worse than proceeding. We decided to push on.

Recommendation: Hug the east side of the pass and stagger if hiking with others, the rock is very loose. Those uncomfortable with steep, unstable terrain should avoid using Harrison Pass.

After an hour of carefully navigating down the eroded slope, we encountered an vast talus and boulder field. Just happy to be on different terrain, we began boulder hopping (never fun with a 2olb pack) on our way to the basin below. On to the second (and thankfully last) off-trail pass of the day, Deerhorn Saddle.

Sitting to the east of Deerhorn Mountain, this Class 2 pass sits above a lush basin with a few small lakes. I’d recommend approaching it from the west. It’s an easy but steep climb up shifting sand to the saddle.

When descending the north slope of Deerhorn Saddle, I’d recommend staying to the right (east) side. The slope was sandy, and we “scree skied” our way down until the loose gravel gave way to talus. Even in mid-September, a few large snowfields still lingered as we approached Upper Vidette Lake.Deerhorn Saddle was no walk in the park, but compared to Harrison Pass, it almost felt like one.

In total, it took us nearly six hours to cover less than five miles, with the rough terrain making every step slow and deliberate. Our efforts did not go unrewarded — Upper Vidette Lake was absolutely breathtaking.

What a sense of relief we felt laying down our packs after a long and trying day. We quickly set up camp and fell into our usual alpine lake routine: a quick swim, a little fishing, and some whiskey. Peak living in my book!

We lingered lake-side well after sunset, grateful to have such a stunning place all to ourselves. I’ll probably never (willingly) use Harrison Pass again, but I was grateful it led us to such a beautiful and remote spot. Upper Vidette Lake might be one of my favorite lakes in all of the Sierra.

After a brisk night, we savored our coffee and the view before packing up and out. With East Vidette serving as our north star, we started making our along the west side of Vidette Creek until we linked up with a use trail that connected to the JMT. But just before reaching the junction, tucked among the pines, we stumbled upon an old trapping shelter from the 1920s — built by the legendary trapper Shorty Lovelace.

Shorty Lovelace

Shorty spent his winters trekking between 36 shelters he built throughout the Sierra while trapping pine martens (Martes americana), until Kings Canyon National Park was established in 1940.

Read this for some fun regional history!

After a brief stint on the JMT, we were back on the trail to Kearsarge Pass. The path was humming with day hikers and backpackers alike, all soaking up a clear, crisp day in the Sierra.

As our car came into view, I felt a pang of sadness knowing I’d have to wait until next summer to hit the trails again. I’ll just be daydreaming until then!